The World Health Organization recently published its analysis about the public health implications of the Nagoya Protocol on genetic resources access and benefit-sharing, and in particular how it affects the sharing of pathogens, like influenza viruses. The findings are set to be discussed at this month’s WHO Executive Board meeting. Also to be discussed is an experts group review of the WHO pandemic influenza framework, and in particular its conclusion that the framework should be amended to match scientific progress.

[Note: a full IP-Watch analysis of the Executive Board agenda is available here (IPW, WHO, 17 January 2017).]

For the 140th Executive Board meeting, taking place from 23 January to 2 February, the WHO secretariat prepared an analysis [pdf] of the public health implications of the implementation of the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization to the Convention on Biological Diversity.

The analysis is based on information-gathering including member states, stakeholders, experts, and various international organisations, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations.

According to the document, the Nagoya Protocol sets out broad principles, and many details are left to domestic jurisdictions, including how to address pathogens in implementing legislation and how to implement health emergency measures.

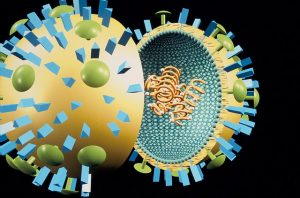

“In the context of influenza, for example, monitoring the evolution and spread of viruses, and responding to outbreaks, is a continuous process, requiring constant access to samples of circulating influenza viruses. This involves the sharing of thousands of influenza virus samples every year, from as many countries as possible, with the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System [GISRS], a WHO-coordinated global network of laboratories,” the document said.

A central conclusion of the analysis, it said, is that the Nagoya Protocol has implications for the public health response to infectious diseases, including influenza, and these implications include opportunities to advance both public health and principles of fair and equitable sharing of benefits.

Responses provided by member states and stakeholders clarified a number of issues, according to the document. In particular, rapid and comprehensive sharing of pathogens and fair and equitable access to diagnostics, vaccines and treatment are key in infectious disease response.

Responses also indicated that the protocol can be supportive of pathogen-sharing, and promote trust and encourage more countries to share pathogens, providing a normative basis for addressing the equitable sharing of benefits arising from their use.

According to the document, in the context of non-influenza pathogens, some respondents said the protocol provides an opportunity for member states “to establish clear, pre-arranged benefit-sharing expectations for access to pathogens that will contribute to the public health response to infectious disease outbreaks.”

Some concerns were voiced that the implementation of the protocol could slow or limit the sharing of pathogens because of the uncertainty of the scope and implementation of the Nagoya Protocol. Also of concern is the high transactional cost of implementing a bilateral system for access and benefit sharing, and the complexity of varying domestic access and benefit-sharing legislations, the document said.

According to the analysis, “many respondents expressed the view that the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness (PIP) Framework for virus and benefit-sharing is or should be considered a specialized international access and benefit-sharing instrument.”

“Such recognition would mean that the Nagoya Protocol’s requirements for case-by-case Prior Informed Consent and Mutually Agreed Terms would not apply with respect to influenza viruses with human pandemic potential,” the document explained. It added that this “could promote ‘legal certainty’ with respect to such pathogens, strengthening the mechanisms of the PIP Framework.”

Review of the PIP Framework: GSD to be Addressed

The PIP Framework, adopted in 2011, was up for review after 5 years. The framework is intended to improve and strengthen the sharing of influenza viruses with human pandemic potential, and to increase the access of developing countries to vaccines and other pandemic related supplies.

The report [pdf] of the 2016 PIP Framework Review Group found that the PIP Framework “is a bold and innovative tool for pandemic influenza preparedness,” and is being well implemented.

The Review Group detailed key issues needing to be addressed, in particular the handling of genetic sequence data. The report also includes comments on standard material transfer agreements 2 (SMTA2) and partnership contributions (IPW, WHO, 23 November 2016).

However, the group found that key issues “must urgently be addressed for the PIP Framework to remain relevant, including the issue of how GSD [genetic sequence data] should be handled under the PIP Framework, and whether or not the PIP Framework could be expanded to include seasonal influenza, or indeed be used as a model for the sharing of other pathogens.”

GSD contain the genetic information that determines the biological characteristics of an organism or a virus.

The group suggested that WHO develops a “comprehensive evaluation model, including overall success metrics” for the PIP Framework, for annual reporting. WHO “should regularly and more effectively communicate the objectives and progress in the implementation of the PIP Framework to Member States, Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) laboratories, industry, civil society, and other stakeholders,” the group also found.

“Communication and transparency should be enhanced around issues such as selection of countries to receive Partnership Contribution implementation support for improved understanding of the PIP Framework among Member States,” they said.

The group also suggested that the director general request members to consider amending the definition of PIP biological materials to include GSD. And they asked that some language in Annex 4 relating to GSD be amended. The current text says, “The WHO GISRS laboratories will submit genetic sequences data to GISAID and Genbank or similar databases in a timely manner consistent with the Standard Material Transfer Agreement.”

They suggested the following amendment: “The WHO GISRS laboratories will submit genetic sequences data to one or more publicly accessible database of their choice in a timely manner consistent with the Standard Material Transfer Agreement.”

The group suggested another amendment on GSD. The current PIP text says, “Recognizing that greater transparency and access concerning influenza virus genetic sequence data is important to public health and there is a movement towards the use of public-domain or public-access databases such as Genbank and GISAID respectively.”

The suggested amendment is: “Recognizing that greater transparency and access concerning influenza virus genetic sequence data is important to public health and use is made of public domain or public-access databases such as GenBank and/or GISAID, respectively.” [italics added]

“It is critical that the PIP Framework adapts to technological developments, and that the Advisory Group produces with urgency recommendations to clarify the handling of genetic sequence data.”

“The Advisory Group should consider asking WHO Collaborating Centres to report on how genetic sequence data are actually handled, with a view to providing information about the operational realities in GISRS in relation to the acquisition, sharing and use of such data, to inform the Advisory Group’s recommendations on the optimal handling of genetic sequence data under the PIP Framework,” they said.

They also suggested that the director general “should enlist the support of Member States to ensure that influenza virus genetic sequence data remain publicly accessible in sustainable databases, to enable timely, accurate and accessible sharing of these data for pandemic risk assessment and rapid response.”

On standard material transfer agreements 2 (SMTA2), which refer to the agreement signed by private parties with the WHO to access influenza biological material from GISRS, the Review Group said the SMTA2s signed so far have secured access to about 350 million doses of pandemic vaccine to be delivered in real time during an influenza pandemic.

However, the group said the PIP Framework options for SMTA2 commitments from manufacturers of other pandemic products, such as diagnostics and syringes, are “too narrow, and need to include a wide choice of commitments.”

According to the report, several industry representatives have remarked on the fluctuation in the amount of partnership contribution they are asked to pay each year, saying that this fluctuation represents budgetary challenges. They indicated they would prefer to pay a set amount, the group said, adding that industry has begun a consultative process to review the partnership contribution formula, working with all relevant industry sectors and the PIP Framework Secretariat.

[…] IP-Watch is a non-profit independent news service, and subscribing to our service helps … recently published its analysis about the public health implications of the Nagoya Protocol on genetic resources access and benefit-sharing, and in particular … ( read original story …) […]

[…] The secretariat prepared an analysis [pdf] of the public health implications of the implementation of the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization to the CBD. The analysis is based on information-gathering including member states, stakeholders, experts, and various international organisations, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. See detailed story (IPW, WHO, 17 January 2017). […]