CHICAGO, Illinois – US President Trump Monday signed the repeal of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) broadband privacy rules passed by both houses of Congress in March. The decision by Congress and the new administration to smash the FCC broadband privacy rules, data security and security breach notification obligations do not bode well for internet users who want to have a say with regard to their confidentiality, according to a range of tech experts.

Intellectual Property Watch spoke with technical experts gathered at the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) in Chicago last week about potential consequences. The IETF since the Snowden revelations has begun making an attempt to add to security and privacy in their protocols.

Business as Usual – the Broadband Provider

The communication operator‘s view tends to picture the new situation as “business as usual” rather than some fundamental new risk for users. “There has been no change at all,” an engineer of an operator who did not want to be quoted told Intellectual Property Watch, at the IETF. For his company, gaining new customers is more important than selling data, he said.

US Telecom CEO Jonathan Spalter in an op-ed at the end of the week emphasised this line: “Consumers wake up today to the same online world and digital protections they enjoyed one week ago.” He warned against user campaigns started after the decision that announced they now would turn the tables and buy the online browsing histories of politicians and publish them online. Plus, the revocation had opened the way for a harmonized privacy regime, that included other services providers, according to the telecom industry lobbyists.

The business as usual statement is true in the sense that the changes of the broadband privacy rules had not taken effect yet. But privacy advocates warn that the rollback prevents a change to protect users better in the future.

It will not allow users to say no to the reuse of their location, browsing or other user data for other purposes. The privacy broadband rules would have obliged telecom companies to ask for an opt-in. Also providers would have been obliged to inform users when their data have been compromised or leaked.

Another Step to Ossify Bad Privacy

“It’s a huge threat for freedom of expression and privacy when we cannot trust channels of communication and the integrity of our messages,” said Niels ten Oever, attending the IETF for Article19, an activist group fighting for rights online. “This development makes it even harder to protect our information, because the ISP is a gatekeeper to the internet, you cannot connect to the internet without it. This means that privacy violations are now the default reality for many American internet users.”

Daniel Kahn Gilmor, defending privacy in the IETF standardization work for the American Civil Liberties Union, added that the biggest threat of the rollback resulted from a procedural point. By withdrawing the FCC‘s rule under the Congress Review Act, the Republican majority made sure that no agency can decide on “substantially similar” rules in the future without US Congress legislating. Kahn said that agencies could be sued in the future over the interpretation of “similar”, “not only by Congress. It also opens the door for companies to file complaints.”

Technical Tricks to Learn about User Behavior

In the days since the House decision, the Electronic Frontier Foundation was quick to dismantle the notion that the legislators did not affect user privacy. The organisation noted, “Verizon has announced new plans to install software on customers’ devices to track what apps customers have downloaded.“ While Verizon was quick to point out it would provide an opt-in, EFF countered the click-through licence foreseen was not sufficient to allow for informed consent for the normal user. With the “spyware” AppFlash, EFF wrote, “Verizon will be able to sell ads to you across the Internet based on things like which bank you use and whether you’ve downloaded a fertility app.”

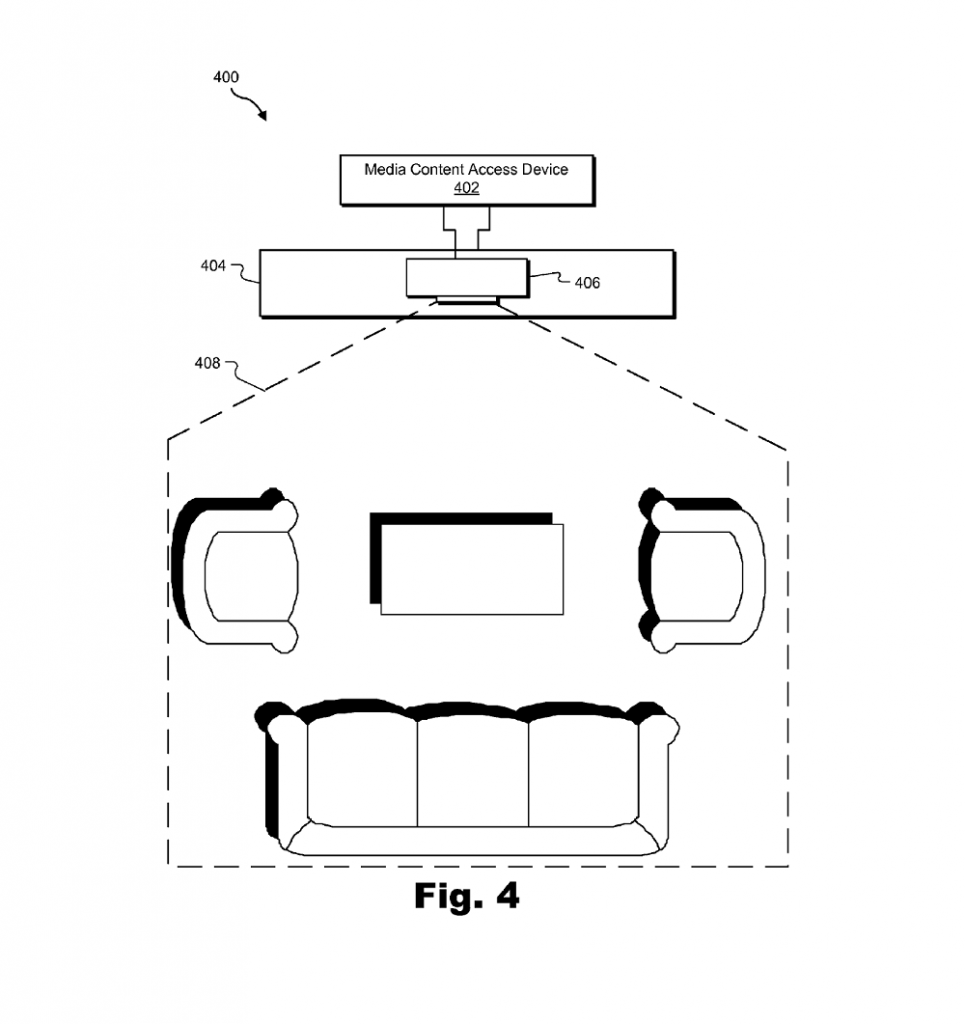

How far broadband providers would like to go in their microtargeting efforts may be seen by looking to a rather scary patent applications from a few years ago. Verizon, one of the broadband providers lobbying for an end to opt-in for users, in 2011 applied for a method to sense ambient noise, figure out what a user – or several users – are doing in front of the TV screen display ads that they thought matched the behaviour.

The “ambient action” according to the patent application may “include the user eating, exercising, laughing, reading, sleeping, talking, singing, humming, cleaning, playing a musical instrument, performing any other physical action.” Examples given for several users interacting, are “the user talking to, cuddling with, fighting with, wrestling with, playing a game with, competing with, and/or otherwise interacting with the other user.” Incidentally, interacting with a mobile device also was an ambient action addressed. The patent was not granted in the end, as too much related technology had been patented before.

Should Human Rights be Part of the “Tussle in Cyberspace”?

Congress using the CRA in that way forced users to see their internet, phone providers as their adversaries who even tried to insert spy technology or hamper with encryption. For users, Kahn Gilmor explained, it resulted in the need to search protection, using Tor or Virtual Private Networks for browsing for example. “Those are the same measures you use to avoid a malicious censor or hide your activity from an oppressive employer,” said Kahn Gilmor.

During the IETF meeting Dave Clark, MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) professor and well-known internet pioneer, challenged the engineers to consider taking on human rights as part of the “tussle” – the negotiation of diverging efforts in cyberspace. Clark said he was supportive of the “values in design movement,” because “technology [is] not neutral.” But to make an attempt to “tilt the playing field,” engineers had to address the issues and design for the tussle to be played out in their technology.

The IETF in an early discussion over legal interception in the US – the so-called Calea legislation – decided to not standardize this, a decision which resulted in the legal intercept technology being built elsewhere. The same is true for TLS, encryption for data in transport, being updated just now in the IETF.

“Are we clever enough to tilt the playing field?” Clark asked his colleagues in Chicago. Ten Oever, who chairs a Human Rights in Protocols Research Group of the Internet Research Task Force (IRTF), the sister organisation of the IETF, asked the IETF to consider starting an IETF working group on the rights issues.

Roll-Back Here, but Roll Forward Elsewhere

The new IETF Chair, Cisco engineer Alissa Cooper, talking to Intellectual Property Watch said on broadband privacy that discussions had been ongoing for a long time on which agency should have jurisdiction and that the related policy and technology debates are ongoing. “Those things ebb and flow,” she said.

“You can look at it from another side, as you might perceive something is rolling back in the US, but you might also perceive that it is at the same time rolled forward in the EU, where there is a ton of activity to shore up privacy with the general data protection regulation and the e-privacy directive.”

The IETF has to look around, derive what the privacy properties are and the security properties are, Cooper said, adding: “We should be cognisant of these things, but that is not building to any specific standard in any jurisdiction.”

The revocation of the broadband privacy rules could very well have one fall-out in the political sphere. On 6 April, the European Parliament will decide if it still thinks the privacy standards in the US are supportive enough to uphold the Privacy Shield, the follow-up rules to allow for transfers of personal data from the EU to the US.

Ralf Bendrath, assistant to Green Party member Jan Philipp Albrecht, lead rapporteur of the GDPR, in a written comment to Intellectual Property Watch noted that while legally the FCC broadband rules were for ISP in the US only and did not cover EU data, the decision was another signal about the serious gaps in privacy protections in the US and the situation seemed to change for the worse. “We have to see the whole picture,” he said.

A decisive majority rule by the Parliament against keeping up the Privacy Shield could oblige the European Commission to consider renegotiation.

Image Credits: Monika Ermert

While there is competition among wireless providers, when it comes to wired broadband how many of you have even two ISPs to choose between? If you lived in Nice, France, you’d have a choice of six internet providers — Americans can’t imagine such a scenario — and your rates would be lower. That’s what competition looks like, and American ISPs are determined to avoid it by carefully carving up the country and creating their monopoly.

We’re meant to trust in the (nonexistent) free market and ISPs’ own pledges to behave. With regard to privacy rules, Verizon recently earnestly vowed: “Verizon is fully committed to the privacy of our customers. We value the trust our customers have in us so protecting the privacy of customer information is a core priority for us.”

This would be the same Verizon that for two years operated a secret tracking and monitoring program that injected undetectable, undeletable “supercookies” into customers’ mobile traffic, without mentioning a word in its privacy policy or giving customers a way to opt-out. After being caught with its hand in the proverbial cookie jar, Verizon issued a statement, saying “we take our customers’ privacy seriously.” Taking this in account, It’s better to take privacy matters into our own hands and use precautionary measures like using a VPN to protect our self from ISPs.

https://www.purevpn.com/blog/how-to-hide-browser-history-from-isp/